The Sinking of the E.M. Clark:

The E.M. Clark was originally the Victolite for Imperial Oil, Ltd. In 1926, the ship joined the Esso fleet and renamed the E.M. Clark.

At the start of the war in Europe on September 3, 1939, the E.M. Clark was commanded by Captain Patrick S. Mahony and the Chief Engineer was Travis L. Lumpkin. On August 27, the ship left Boston and arrived in Baton Rouge on September 4. The ship was loaded with 114,799 barrels of East Texas crude. This was one of many trips made the rest of 1939.

In 1940, the ship made 13 voyages, including trips to Aruba, Buenos Aires, Guiria, and Las Piedras. In 1941, it was part of the Gulf-Atlantic coast service except for their last assignment of the year to take gasoline to Santos, Brazil. When the United States declared war against Japan on December 8, 1941, the E.M. Clark was in the Gulf of Mexico, having left Baytown Texas at 1:24 P.M on December 7. On the 8th of December, she received a warning message that a German raider was in her path. Shortly thereafter, a British auxiliary cruiser, hunting for enemy ships, circled the E.M. Clark with guns pointed at her until the tanker gave her name, cargo, and destination.

The E.M. Clark was a part of a fleet of ships that transported petroleum products to support the Allies during WWII. The ship made 41 voyages from 1939 to 1941, transporting over 4 million barrels of petroleum products. Prior to its own sinking, it had come in contact with Geman U-boats. On January 24, 1942, they picked up a distress call from the Venore when the ship was torpedoed off Cape Hatteras on that day. They were ten days out of Santos and due to arrive in a few days at Caripito. In 1942, the E.M. Clark had completed two voyages from Caripito and Aruba to Baltimore and from Baytown and Texas City to St. Rose. Louisana.

On March 11, 1942, the E.M. Clark left Baton Rouge, Lousiana carrying 118,725 barrels of heating oil that were destined for New York.

As the ship headed north heading toward the Diamond Shoals, Captain Hubert Hassell, kept his crew on high alert the evening of March 17, 1942. At that time the airwaves were full of distress calls from two of Johann Mohr's (U-124 Captain) attacked ships, the Acme(didn't sink) and the Kassandra Louloudis (sunk). As she traveled alone on a track recommended by the Naval Routing Officer at New Orleans. The ship was blacked out, all ports were closed, and the navigation lights were turned off. There was no weaponry aboard the tanker.

It was a nasty night as the rain was falling at a steady pace, squalls had the sea running rough, and lightning was lighting up the sky. To make matters even tenser there was the sound of thunder heard throughout the night. With all of this activity, the captain didn't settle into his stateroom until after midnight.

The following is an account taken from the reports of Captain Hassell and Radio Operator Earle J. Schlarb. This is a fascinating first-hand report that I found in the book, Ships of the Esso Fleet in WWII.

According to Captain Hassell's report: "On March 17, at 8 p.m., the weather became squally with lightning and rainfalls and wind southwest-Force 4-sea moderately rough. At about 12:35 a.m., March 18, I had retired to my stateroom. Second Mate Richard F. Ludden was in charge of the bridge. An A.B. was at the wheel; Lynn Bartee, O.S., was on lookout at the foc'sle head; and an A.B. was on standby.

"Immediately after the explosion, I proceeded to the bridge where I took charge from the second mate, who had already sounded the general alarm and ordered the engines 'Full astern' and then 'Stop'. These orders were promptly complied with.

"I then went to the radio operator's room and assisted him in the attempt to rig the emergency antenna in order to send an SOS. as the regular antenna had been destroyed."

Radio Operator Earle J. Schlarb. in his statement submitted for this history and in comment during an interview, described his experience during the emergency-when "seconds seemed like minutes and minutes like hours."At midnight," he said, "I threw in the switch for the automatic alarm and glanced about 'the radio room, making a general check-up before going off watch. My life jacket was hanging on the doorknob. Taking my radio operator license out of the frame and placing it where I could get it quickly if need arose, I went below to get some sleep.

"The auto alarm' bell in my room was ringing madly when I awoke, finding myself halfway out of my bunk. I hurried into my clothes and snatched up a flashlight. As I opened my door I breathed in the sharp, acrid odor of burnt powder in the companionway. Rushing up to the radio room, I turned on my flashlight and found the whole place in chaos. Parts of the apparatus, the filing cabinet, spare parts locker, table, and racks were in a tangled heap on the floor. The typewriter had been flung across the operating chair and table and had crashed into the receiverbattery charger. The door leading to the boat deck had been blown off and part of the bulkhead was gone.

"Feeling lucky to be alive, I pulled the auto alarm switch and stopped the clamor of the bells. Then I heard the captain saying, 'Sparks, get on the air!'

"There was no ship voltage, as the power lines were broken; that was why the alarm bells rang. A battery started them when the line voltage fell below normal. Immediately I threw in the battery switch for the emergency transmitter power supply. It worked! Then I connected the antenna transfer and telegraph key switches and 'sat on the key', sending and repeating SSSS-SOS. But there was no radiation on the dial. Had the main antenna been broken?

"Going outside to the boat deck, I stumbled in the darkness over more wreckage. A flash of lightning showed the damage done by the torpedo; the lifeboat was a blasted heap of torn and twisted metal and splinters; a jagged hole yawned in the sagging deck. Awning and stanchion bars were smashed off or hanging loosely.

"When the lightning passed, inky blackness shut-in tightly. I could not see whether the mainmast was still standing. Feeling my way by flashlight, I crossed to the starboard side and bumped into the first assistant engineer, who was coming up from aft. I asked him if the mainmast was down. 'Damned if I know,' 'he· said, 'but the deck is full of wires. Your antenna must be broken! '"Another flash of lightning revealed the starboard lifeboat being prepared for launching. Some of the men were in it, others on deck. I returned to the radio room, put on my life jacket, and grabbed the coil of spare antenna, tangled by the explosion, but intact. As I backed out on deck, trying to straighten out the wires, it was a matter of great urgency to find a place to attach the emergency antenna. I thought of the small runway atop the radio room, with a ladder leading up to the wing of the monkey bridge. Somehow I grasped the top of the sheer bulkhead, pulled myself up, and bent one end of the tangled antenna wire around the iron railing.

"Suddenly, off the port side of the ship, distant about 300 yards, a submarine's yellow searchlight was turned on and played about the E. M. Clark, apparently to inspect the damage caused by the torpedo.

"Someone approaching me called out 'Sparks'. I answered with a shout and up came Captain Hassell and Second Mate Ludden. 'The antenna is down,' I said. 'Here is the spare coil of wire. It's badly messed up. Can you give me a hand?' I scaled the bulkhead again and unhooked the wire. All three of us started pulling and twisting. A considerable length came free and I climbed with it up the ladder to the bridge wing. Part of the awning bar was still up. To get the spare antenna as far out from the ship's house as possible, I inched along in the murky dark, holding the rail with one hand, the wire with the other. As if by instinct, I halted where I found the railing gone. At the same instant, a bolt of lightning showed that the outer wing of the bridge had been torn off. Blackwater and wreckage gleamed up from far below. One step farther ... . I could feel my heart beating as I made one end of the insulator fast to the swaying, broken awning bar. When I went back· on deck, the captain told me the lead-in was free. We ignored the rest of the tangle, pulled taut what we had, and hooked up the lead-in to the bulkhead insulator.

"I had hardly started for the radio room to send distress calls when the ship leaped and shuddered. The lead-in was torn from my hands. Captain Hassell, thrown off balance, stumbled and dropped his flashlight as the sound of a dull, heavy explosion reached our ears. Hit again! This time it was up forward, in way of No. I tank and the dry cargo hold. The torpedo had apparently gone deep inside before detonating.

"The ship's whistle jammed and sent forth a steady roar. Broken steam lines hissed loudly. The captain found his light and turned it on. The glass was broken but the bulb still worked. The second mat???? ran to starboard to see if No. I lifeboat was still intact.

"I thought it had started to rain but what I felt on my face was not water; the 'rain drops' were oil! Cargo heating oil had been blown high and was falling in a fine spray! It seemed a miracle that the ship had not caught fire. The explosion had ripped down the spare antenna we were working on and part of it could not be seen.

"The second mate came back, holding the rail as the ship took a list to port. 'Captain,' he shouted, 'she's going down fast!' Captain Hassell looked at me. 'How long will it take to repair this and send an SOS?' he asked. 'At least 15 minutes, maybe more,' I replied. 'The insulator here is broken and the one above, also. Part of the wire is gone. The rest must be unraveled.' Captain Hassell said calmly, 'I doubt if we have 15 minutes.' "

Returning to Captain Hassell's report:

"I gave orders to launch the lifeboats and abandon the ship. No 2 boat had been destroyed; 14 men got into No. I boat and 26 in No. 4. Thomas J. Larkin, utilityman, was the only missing crew member when I made the count and it is presumed that he was killed by the first explosion while asleep in the hospital room, about where the torpedo struck.

"Before going into No. I boat myself, I collected the ship's documents and secret wartime codes. Taking the former along with me, I threw the codes overboard in a weighted canvas bag."

To continue the radio operator's story:

"When we went over to No. l, the captain and I handled the after fall while the second mate and others took care of the gear forward. Captain Hassell, believing all hands were accounted for, was the last man to enter the lifeboat. Although we were on the windward side, the boat was safely launched, but once it was in the water the trouble started, as the wind and waves slammed us against the ship's side with great force. All hands worked hard trying to shove off, using the heavy oars and boat hooks. Finally, we got the boat clear and all the oars in the water. Rowing was difficult because of the choppy waves and the rolling of the lifeboat.

"Suddenly a seaman yelled and pointed to a man standing at the ship's rail. Captain Hassell directed us to pull back partway, and shouted to the man to jump. His orders were muffled by the din of the ship's whistle. The man on the deck, Wiper Glen Barnhart, slid down a boat fall and dropped into the sea. He wore a life jacket but weighed about 240 pounds and floated low in the water. A wave picked him up and tossed him within a few yards of the lifeboat. He was soon hauled aboard and covered with a blanket.

"The captain told us to row around the stern of the vessel to see if anyone else could be picked up. We had just started when the loom of light showed, creeping around the ship's stern. 'It's the sub!' someone called out. 'Let's get the hell out of here!' The captain gave orders to puH away and wait until the enemy U-boat submerged. We saw the submarine heading for the stern of the ship as its yellow light silhouetted the torpedoed tanker in the darkness.

"The E. M. Clark was then deep down by the head and filling rapidly. The sea was covered with oil, which kept the waves from breaking over our life. boat, but the fumes were sickening. Several of the men-I was one of them became violently ill.

"The ship's stern began to lift high as she plunged forward and down. Just before the smokestack disappeared under the surface, the whistle, which had been blowing steadily since the second explosion, stopped for about IO seconds, then started again.

"A great bubbling noise was heard as the E. M. Clark slid smoothly beneath the waves,

"Now that the ship was gone, we could see the entire length of the searchlight beam, but it was too dark to distinguish the U-boat's hull or conning tower.

"'Keep circling her,' ordered the captain. 'When she dives we'll see if we can find anyone.'

"A black shape now came alongside. It was one of the life rafts, which Chief Mate Andrew Kadek had released, between torpedo hits, at the risk of his life. A shark, possibly killed by the concussion, floated by, white belly up.

"We rowed until the lifeboat was out of the oil slick. The waves were now six to eight feet high and all hands were busy with the oars, keeping the boat's head into the wind. The captain called for a count and 13 men reported.

"The submarine's course could be followed by its light, which kept swinging back and forth over the place where the ship had sunk. Now and then the searching beam passed over our boat, but each time this happened we were hidden by wave crests. About two hours later the sub disappeared. The captain then ordered the sea anchor put out to keep the boat from broadsiding to the seas and shipping water. We saw no sign of lifeboat No. 4. Rain started to fall again and those who had not had time to put on warm clothing began to suffer from the cold.

"Our lifeboat drifted till just before dawn when the compass was broken out to determine the direction of the nearest land. As the wind was blowing toward shore, a sail was hoisted and we moved along at a good clip before a stiff breeze.

"As the first gray streaks of dawn crept over the sea, several ships were sighted far off. At about 7 a.m., a destroyer appeared over the horizon. We shot two red flares and she changed course. A few minutes later another flare was fired and before long the destroyer neared us, maneuvered to windward, and carefully came alongside. After five hours in the lifeboat, we were soaking wet with rain and spray and chilled by the cold wind. When we were picked up, it felt mighty good to be safely aboard a United States man-o'-war-the USS Dickerson.

"No definite word of No. 4 boat was received for some hours. Finally, the Dickerson sighted an empty lifeboat containing several pieces of discarded wearing apparel. It was No. 4 boat of the E. M. Clark. We later learned that the 26 men in this boat had been rescued by a Venezuelan tanker and landed at Norfolk."

Captain Hassell concluded his report as follows:

"In the afternoon we were transferred to a Coast Guard cutter which landed us at a nearby station. From there we proceeded to Atlantic, N. C., thence to Morehead City, and finally to New York, where we arrived March 20."

One final thought about the crew of the E.M. Clark is that if you look at the crew members listing below, you'll notice the number of people that were on other ships that were sunk by German U-boats. Of the list, four members of the E.M. Clark were killed when attacked on their next ship assignment. I often wonder how those men that went through this once handled it, but to go through a sinking twice!

THE SHIP'S SPECIFICS:

| Built: 1921 | Sunk: March 18, 1942 |

| Type of Vessel: Tanker | Owner: Standard Oil Company of New Jersey |

| Builder: Federal Ship Building Company, Kearny, NJ | Power: Oil-fired steam |

| Port of registry: Wilmington, DE | Dimensions:499' long x 68' wide x 30' deep |

| Previously Known: Victolite |

LOCATION OF THE SINKING:

Here is the location of the sinking: 34° 50'N, 75° 35'W

LOST CREW MEMBERS :

Total Lost: 1, Survivors: 40

| Last | First | Date of Death | Position | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larkin | Thomas Joseph | March 18, 1942 | Messman | Elmhurst, NY |

SURVIVING CREW MEMBERS :

A partial listing of the surviving crew:

| Last | First | Position | DOB | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arney | Porter Cullum | Wiper | Mar. 22, 1898 | Willow Grove, TN | 43 |

| Barnhart | Glenn | Wiper | 1895 | 57 | |

| Bartee | Lynn M. | Ordinary Seaman | June 12, 1918 | Madisonville, TX | 23 |

| Bloom | James | Oiler | |||

| Breitbach | William Robert | Ordinary Seaman | Oct. 22, 1924 | Washington, D.C. | 17 |

| Cichon | Bernard | Fireman/Watertender | July 19, 1913 | Baltimore, MD | 28 |

| Cipy | Pete | Fireman/Watertender | Sept. 2, 1922 | Baltimore, MD | 19 |

| +Dean | Eri Festus | Pumpman | March 24, 1909 | Quincy, FL | 32 |

| Ferguson | Frank W. | Able Seaman | 1906 | 36 | |

| Ferreira | Henrique | Chief Cook | 1907 | 35 | |

| *Gallego | Eugenio Montes | Able Seaman | June 3, 1910 | Houston, TX | 31 |

| **Gonsalves | Eugenio J. | Second Cook | Nov. 12, 1901 | New Bedford, MA | 40 |

| Gray | Jack H. | Storekeeper | 1918 | 24 | |

| Hansen | Edgar | Oiler | |||

| Hassell | Hubert Lovelace | Master/Captain | Nov. 2, 1896 | Queens, NY | 45 |

| ***Hester | William Guy | Able Seaman | Jan. 7, 1910 | 32 | |

| ****Kadek | Andrew | Chief Mate | July 17, 1895 | New Brighton, NY | 46 |

| +++Lafo | Joseph Francis | Chief Engineer | May 28, 1894 | West Haven, CT | 47 |

| Leo | David Wales | Ordinary Seaman | Sept. 15, 1923 | Washington, D.C. | 18 |

| Ludden | Richard Faxon | Second Mate | Jan. 2, 1916 | Abington, MA | 26 |

| *****Menapace | Russell Lang | Able Seaman | June 15, 1913 | Baltimore, MD | 28 |

| Mercado | Paul R. | Oiler | 1920 | 22 | |

| Miller | James W. | Wiper | 1896 | 46 | |

| ++++Montemayor | Magno D. | Messman | 1910 | 32 | |

| ******Muller | Charles | Third Mate | Aug. 8, 1895 | Bayonne, NJ | |

| O'Neal | James H. | Oiler | |||

| Pace | Hollis C. | Able Seaman | Feb. 15, 1902 | East Baton Rouge, LA | 40 |

| Reber | William Vernon | Second Assistant Engineer | March 26, 1887 | Natchez, MS | 54 |

| Rew | Harold Elwyn | Boatswain | Aug. 7, 1922 | Baltimore, MD | 19 |

| Rollason | Fred | Steward | Sept. 14, 1896 | Baltimore, MD | 45 |

| *******Schlarb | Earle Joseph | Radio Operator | Aug. 1, 1915 | Chicago, IL | 26 |

| ********Stafford | James T. | Able Seaman | 1920 | 22 | |

| Turner | Henry | Able Seaman | |||

| Walker | David H. | Third Assistant Engineer | 1913 | 29 | |

| Walsh | Thomas G. | Messman | 1903 | 39 | |

| Watkins | Owen Wilson | First Assistant Engineer | Feb. 10, 1884 | Birmingham, AL | 58 |

| *********Wilamoski | Mitchell | Messman | Oct. 18, 1917 | Wesleyville, PA | 24 |

| Williams | Lawton Mack | Oiler | April 29, 1917 | New York, NY | 24 |

| Woods | Wyatt | Oiler | March 2, 1915 | West Feliciana Parish, LA | 29 |

| Worcester | Dowin B. | Fireman/Watertender | Feb. 22, 1905 | 37 |

+Died on April 16, 1944, on the Pan Pennsylvania when the ship was torpedoed and sunk by German U-boat U-550.

++Died on May 28, 1942, on the Alcoa Pilgrim, when the ship was torpedoed and sunk by German U-boat U-502.

+++Died on June 5, 1942, on the L.J. Drake when it was sunk by German U-boat U-68.

++++Died on May 12, 1942, on the Virginia when it was sunk by German U-boat U-507

*Was onboard the Esso Baton Rouge when it was sunk on Feb. 23, 1943.by German U-boat U-123.

**Was onboard the John Worthington when it was sunk on Mary 28, 1943 by German U-boat U-154.

****Was onboard the M.F. Elliott when it was sunk on June 3, 1942, by German U-boat U-502 and was onboard the S.B. Hunt when it was sunk on July 7, 1943 by German U-boat U-185.

*****Was onboard the J.A. Moffet, Jr. when the ship was sunk on July 8, 1942, by German U-boat U-571.

******Was onboard the S.B. Hunt when the ship was sunk on July 7, 1943, by German U-boat U-185

********Was onboard the Benjamin Brewster when the ship was sunk on July 10, 1942, by German U-boat U-67

*******Was onboard the Arriaga when the ship was sunk on June 23, 1942, by German U-boat U-68

*********Was onboard the Richard. D. Spaight when the ship was sunk on March 10, 1943, by German U-boat U-182.

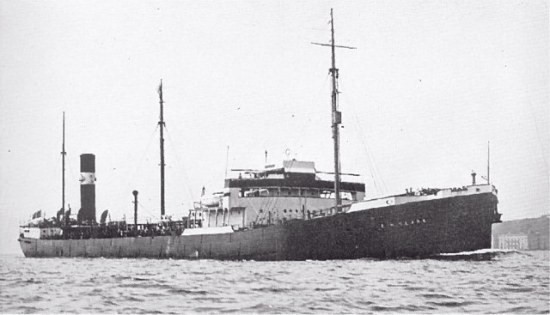

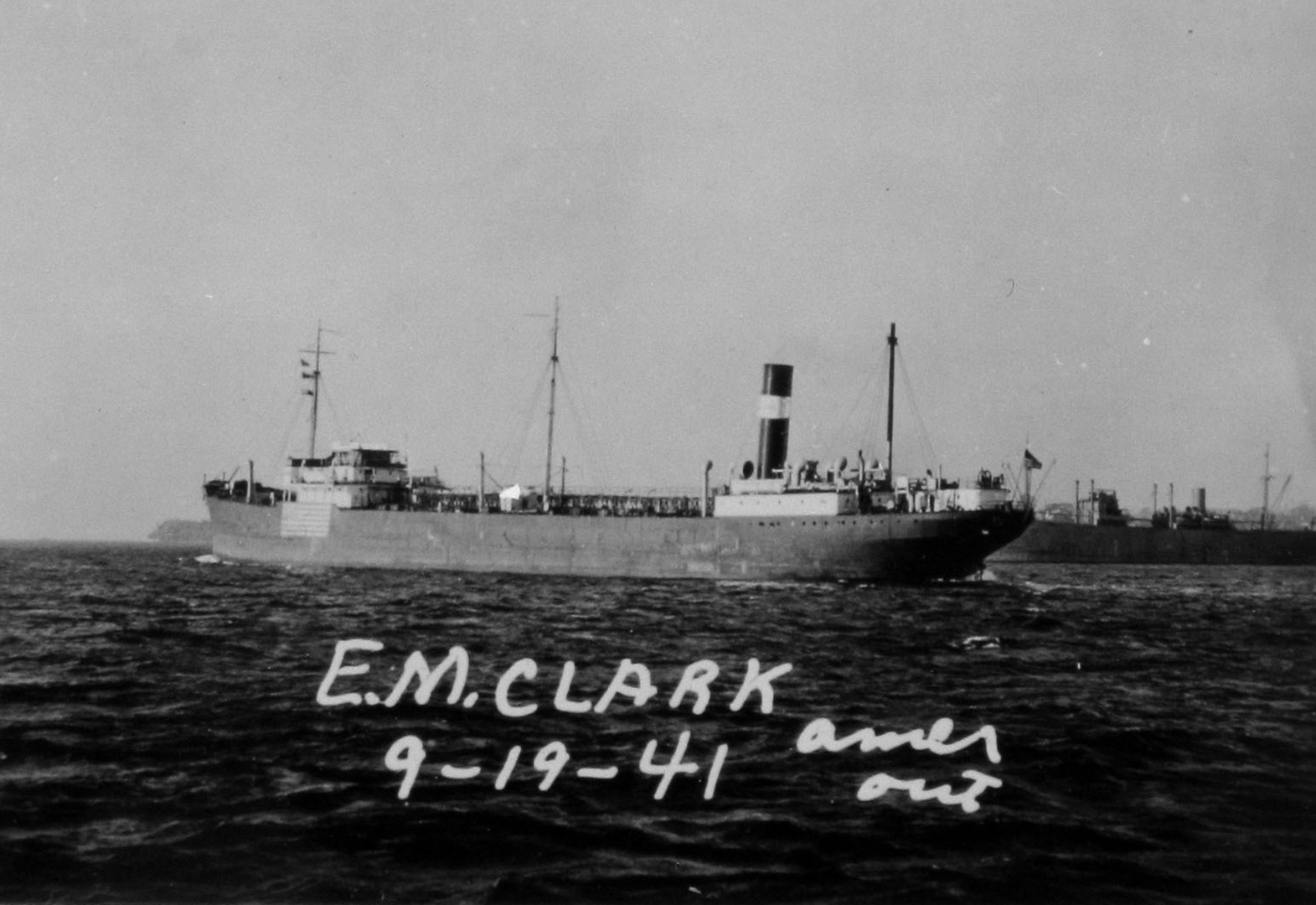

Photos of the E.M. Clark:

|

|

E.M. Clark's fantail stern and starboard propeller. Photo courtesy of Casserley, NOAA |

Bow of E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of Becky Schott, WHOI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

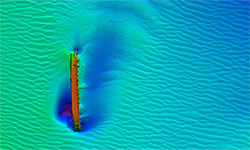

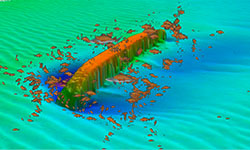

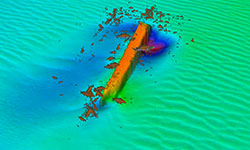

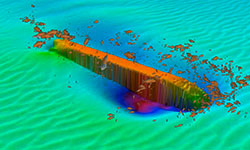

Survey image of E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of NOAA |

Survey image of E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of NOAA |

|

|

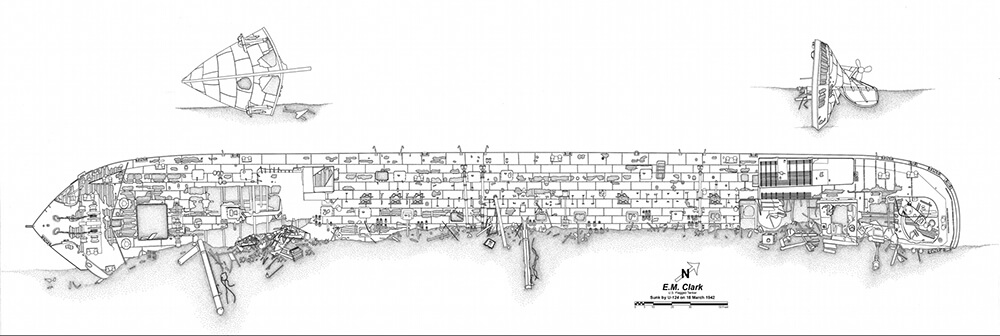

Final archaeological site plan of E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of NOAA. |

|

Diver surveys E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of Hoyt, NOAA

Diver surveys E.M. Clark. Photo courtesy of Hoyt, NOAA