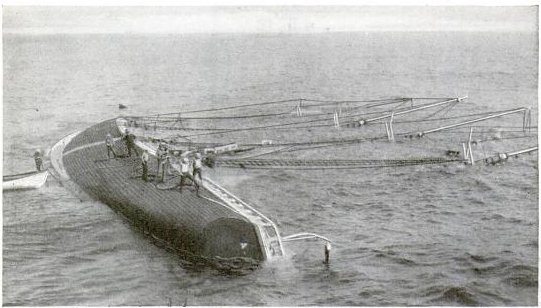

A. Ernest Mills sank after a collision off the coast of North Carolina. Four days later it came to the surface again.

The Sinking of the A. Ernest Mills:

An interesting aspect of researching the sinking of the A. Ernest Mills was when I came across a lawsuit, New England Maritime Co. vs. the United States. It was dated January 14, 1932, and was case numbers 218, 205, 243, 244, 266, and 333.

The report indicates that the collision occurred on April 4, 1929, at 9:00 PM, off the North Carolina coast between the A. Ernest Mills and the United States destroyer Childs. The A. Ernest Mills was on a voyage from Turks Island, W.I. to Norfolk, Virginia with a cargo of salt. It was under the command of Arthur C. Chaney with George A. Carver as his first mate. There was also a crew of seven "colored" men according to the lawsuit.

Here is how it was reported:

"The collision occurred at 9 o'clock in the evening, April 4, 1929. The schooner alleges that there was a haze with fair visibility, the least visibility that existed during the night; that the schooner had an able seaman stationed on the forecastle head, another able seaman at the wheel, a master on the quarter deck, and a first mate and second mate, the latter an able seaman, near the mizzen rigging; that she carried a green and red running light and a white stern light, all lighted by electricity; that there is no claim that her sails, as they were trimmed, could obscure her running light. While proceeding off Currituck Light, N.C., a little after half past 8 in the evening of April 4, 1929, the navigators of the Mills saw in the distance the yardarm blinker lights of several vessels which they thought to be United States naval vessels, and which later proved to be the destroyers Coghlan, Childs, and Bruce. The libelant alleges that the senses of all on board the Mills were aroused to the danger confronting the schooner, although the fact that no running lights or even a masthead light was yet visible indicated that the war vessels were a considerable distance away, estimated by witnesses on the schooner to be about eight or ten miles distant; that at this time, about fifteen to twenty minutes before the collision, the first mate, Carver, under orders of Captain Chaney, changed the 15-watt bulbs of the running lights to 25-watt bulbs; and that precautions were taken to see that both the red and the green lights were burning brightly.

It appears from the proofs, as stated by the government, that the three destroyers, Coghlan, Childs and Bruce, on April 4, 1929, were bound for Guantanamo, Cuba, to join the fleet for naval maneuvers. As sister ships of the same general design, the destroyers were about 300 feet long, 30 feet beam, and drawing means 12 feet 2 inches. They were proceeding information, with the Coghlan leading, the Childs about 30 degrees on her starboard quarter, distant 1,200 to 1,500 yards, and the Bruce in the same position on her port quarter, with a distance of about 1,200 yards between the Bruce and the Childs. Their speed was 18 knots and their course 160 true, after 7 o'clock. Each was equipped with a gyro-compass reading the true course. Each carried two range lights on the foremast and mainmast and red and green sidelights. Each of these lights was a powerful light. The deck watch of each of the destroyers as they approached the schooner was: On the Coghlan, Commander Moran, senior officer of the squadron and in command, who graduated from the Naval Academy 1910, with eighteen years' sea experience on battleships, gunboats, and destroyers, and six years in command of destroyers; Lieutenant Griffin, who graduated from the Naval Academy in 1927, and on the Coghlan since May, 1928, with the assignment of deck watch officer for the eight months prior to the collision; Lieutenant Sedgewick, navigating officer, who had been going to sea continuously as officer of the deck on naval vessels of all kinds since 1918, save for shore duty 1925-26; starboard lookout, Whelan, age 22, who had been with the destroyer for a year and two months, acting as lookout about eleven months before the collision; port lookout, Coombs, age 23, who had been on the Coghlan for about a year and had stood watch for over eleven months, having the rating of a seaman, second class; Steersman Breen, Signalman Johnson, and Messenger Warrick. The deck watch of the Childs was as follows: Officer of the deck, Lieutenant Johnston, graduated from the Naval Academy June 3, 1926, joined the United States steamship Arkansas as junior watch and division officer September 1926, to July 1927; communication watch officer, steamship Arkansas March 5, 1928, and joined the Childs March 5, 1928; previous to the collision he had served as officer of the deck thirteen months. Majors, starboard lookout, age 26, seaman second class; had stood watches aboard the Childs over three hundred periods from the time he joined the Childs in April 1928. Strong, port lookout, seaman first class, with navy since 1925, upon sea duty. Zak, signalman, age 25, attached to the Childs for five years. Anderson, wheelsman or quartermaster, who had been by the Childs for two years, four months, during which time he had been acting as wheelsman for sixteen to eighteen months.

It appears that the three destroyers were navigated and operated solely from the bridge. The place of the collision was in the usual line of traffic of all vessels bound north and south of Hatteras. While proceeding at the speed of 18 knots, it appears from the proofs offered by those on the Coghlan that a white light was seen in the path of the apex destroyer Coghlan, which proved to be a light on the schooner Mills bound on a course about opposite that of the Coghlan; and in about six minutes from the time this white light was first sighted by those on the Coghlan the green light and the loom of the sails of the Mills were seen by Commander Moran and the officer of the deck insufficient time for the Coghlan to be put under hard left rudder and leave the schooner Mills about 200 yards on the starboard side. The Coghlan immediately signaled by blinker to the Childs, "Sailing vessel close aboard." The Coghlan then at once put a spotlight on the sails of the Schooner. The Childs acknowledged receipt of the signal, but kept on at 18 knots, neither stopping nor slowing. The Childs appears to have made no attempt to keep clear of the schooner until she was upon her. Then, seeing the schooner approximately dead ahead, the Childs executed hard right in an attempt to cross the bow of the schooner, and also gave the order to reverse her engines. The bow of the Childs struck the schooner between the main and mizzen rigging, cutting through the vessel and cargo, beyond her keel, and causing her to sink in about three minutes, carrying down with her the master, the cook, and one seaman.

The government urges that the navigating officer and the officer of the deck on the Coghlan were using powerful marine glasses when they first observed the dim white light dead ahead; that three officers testified that the light seemed to them to have no characteristics except a dim white light dead ahead which, under article 1 of the International Rules, would indicate a vessel proceeding in the same direction and some distance off; that the officer of the deck, exercising great care and with powerful glasses, kept the dim white light in sight, and that he next saw the loom of the sails of the schooner about 200 yards off, and shortly afterwards picked up a dim green light; that he recognized then that the white light proceeded from what he says looked to him like a lantern on deck; that the port lookout on the Coghlan first observed a dim white light on the schooner when she passed close aboard about 100 to 200 yards distant; that he recognized the loom of the schooner and never saw a green light upon her at any time; that the starboard lookout also saw the form of the schooner, observed only a white light, and says he did not see a green light; that, though Commander Moran and Officer Griffin saw the green light and the sails of the schooner in sufficient time to left rudder and leave the schooner about 200 yards to starboard, the light appeared to the commander to be dim.

In the case before me these officers were sailing the three destroyers in the nighttime, along the path of commerce, in a triangular formation, making a sweep of about a half-mile in width, and at a speed of 18 knots. While so proceeding, they were taking upon themselves a great burden of responsibility. These highly trained navigators must have realized that, unless they observed very strict care they might become a menace to other ships, as certain submarines were held to be by Judge Hand. While proceeding as described, the officer of the deck of the Coghlan observed a white light ahead, some distance off, which was thought to be a vessel sailing in the same direction; but the Coghlan kept on, and the squadron kept on, at the same speed and on the same course. The officer next saw the loom of the schooner's sails about 200 yards off, and shortly afterwards picked up what he described as a dim green light. He then saw what "looked like a lantern" on the deck of the schooner Mills; and there is further testimony that a lantern was seen. Whether it was in fact a lantern does not clearly appear; and the proofs on the part of the schooner are to the effect that, when the naval vessels were seen to approach, Captain Chaney became nervous and procured a flash-light which threw a white light on the lee side of the spanker, to attract the attention of the approaching ships (as was done in the case of The Prinz Oskar [C.C.A.] 219 F. 483, 487); that Captain Chaney held the light in his hand on the starboard side at the after house in the place where the men on the destroyer say they saw it. After seeing the white light, according to their own testimony, the destroyers continued their approach. The Coghlan leading came close to the schooner, saw her green light and swerved to her left, green to green, clearing the schooner, as those for the schooner say, by about 600 feet. At the same time the Coghlan threw a spotlight on the schooner and sent a special message to the Childs, "Sailing vessel close aboard." The signalman of the Childs received the message, shouted it out word for word to the bridge, and acknowledged it to the Coghlan; but the Childs made no change in her course or speed. Johnston, the young officer on the Childs, testifies that when he heard the message from the Coghlan, "Sailing Vessel Close Aboard," he realized that the danger was especially to the Childs, rather than to the Bruce, and that he knew she was going either in the same direction or an opposite direction from the Childs, and with that understanding he gave the order "hard right" and slowed down. It appears then that instead of turning to the left, as the Coghlan did, he ordered "hard right" and turned across the schooner's bow and at the same time gave the bells to stop and reverse. There is testimony that the men on the Childs did not see the spotlight of the Coghlan. This light was seen by the Bruce. It is contended that the light was not visible on the sails of the schooner because it was shot on the windward side of the spanker; but I think it must have been visible to a vigilant lookout upon the Childs. I think the Childs was clearly in fault for not keeping clear of the schooner. When the light was first seen ahead by the Coghlan, I think, in the exercise of good seamanship, the Coghlan should have slackened her speed and have caused the speed of the squadron to be slackened, even though the light appeared to be from a vessel going in the same direction. It was in the nighttime, upon an ocean highway. The squadron and the schooner were approaching at the rate of a mile in about two and four-tenths minutes, occupying a great space in the path of commerce. From that minute, every one of the few passing minutes was adding to the danger of her approach. After the Coghlan had passed to the left of the schooner and had sent the special signal to the Childs, "Sailing Vessel Close Aboard," the Childs was clearly at fault in that she did not slacken speed. If she had done so, I think the tragedy would have been averted. Speed was a very vital element. Commander Moran testifies that he thinks, if the Childs had been about five seconds slower there would not have been any collision, although in his opinion the schooner should have changed her course. I think, then, that the Childs was plainly at fault for not keeping clear of the Mills, either by slowing down from 18 knots' speed before coming up with the Mills or by not stopping or turning to her left after receiving the Coghlan's signal. I think in not reversing her engines earlier, and in her attempt to cross the bow of the Mills, as she did, she was in violation of the International Rules, articles 22 and 23."

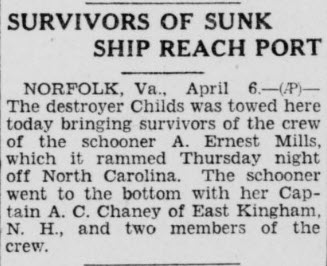

A. Ernest Mills Sinking Article- Brownsville Herald, April 6, 1929

A. Ernest Mills Sinking Article- Brownsville Herald, April 6, 1929

Here is how the Suffolk News-Herald reported it on April 7, 1929:

Paint Graphic Picture Sea Tragedy

Officers of The Destroyer Childs And Members of Crew of Schooner A. Ernest Mills Testifies As to Sinking of the Latter. NAVAL COURT HOLDS AN ALL-DAY SESSION Crash Came Daring Ten Minutes Commander Half Was In His Room Making Out Orders Rut Rushes to Rescue of Doomed Vessel

NORFOLK, Va„ April 6 (AP)-Graphic pictures of those ten minutes Just before 9 o'clock Thursday night when the American schooner A. Ernest Mills was sent to the bottom by the speeding prow of the destroyer Childs, 12 miles off Currituck Light on the North Carolina coast, were painted today before the all-day season of the naval court of inquiry into the disaster. sitting in the office of Rear Admiral W. T. Cluverlus, commandant of the Norfolk navy yard and president of the court.

Lieutenant Commander John Lessie Hall. Jr., the skipper of the Childs; Ensign H. D. Johnston, an officer of the deck at the time of the collision, and lieutenant Commander Thomas Moran, skipper of the Coghlan, which narrowly averted a collision with the schooner a few minutes before she was struck by the Childs, were named by the court as the three "defendants” in the case. It was explained by Admiral Cluverlus that the term “defendant” In a naval board of inquiry Is In no way related In meaning to the similar term to a civil court, but means "that these men have an Inters*, to the case but their action and their testimony are to no way under censure by this^body.”

The court convened this morning at 10 o'clock .commander Hall was the first to take the stand. He said that at ten minutes to 9 o'clock he left the bridge to go to his room to make out his night orders. A few minutes later he felt his ship strike an obstruction with great force. He said he ran to the bridge and found the Child's rammed half through a four-masted schooner, with all sails set, at a point between the main and the mlxxen masts. He said he gave the order of full speed ahead to hold the Child's to the breach, and with a megaphone shouted to the crew of the schooner that he would hold the ship so and ordered them to climb aboard.

Ensign Johnston and George Arthur Strong, seaman second class, the part lookout on the Childs, testified that they saw no lights aboard the schooner either before or after the collision.

George A Carver, of Celias, Me., first mate of the A. Ernest Mills, testified the vessel carried running, mast, and stern lights. High-powered bulbs than those to use before had Installed on the schooner 20 minutes before the crash, he said.

Commander Moran, who was a senior officer of the detachment of three destroyers proceeding from Norfolk to Guantanamo Bay, stated that at about 8:55 o'clock he was on the bridge of the Coghlan when hit lookout reported a light on the port bow. It was a single white light, he said and apparently quite distant, running In a parallel course. A moment later the officer of the deck shouted that the light was changing course. Commander Moran gave orders for a change at the course and the Coghlan cleared the schooner by 200 yards, he estimated.

Lt. Commander J, L. Hall, Jr, who was In command of the destroyer Childs, which ran down and sank the schooner A. Ernest Mills, Is a son of the late Dr. John Leaslle Hall. English professor In the College of William and Mary. He is a native of Williamsburg, where his mother and other relatives now live. He is considered a very capable officer.

THE SHIP'S SPECIFICS:

| Built: | Sunk: April 6, 1929 |

| Type of Vessel: Schooner | Owner: New England Maritime Company |

| Builder: | Power: |

| Port of registry: Wilmington, Delaware | Dimensions: 190.3' x 37.4' |

| Previous Names: |

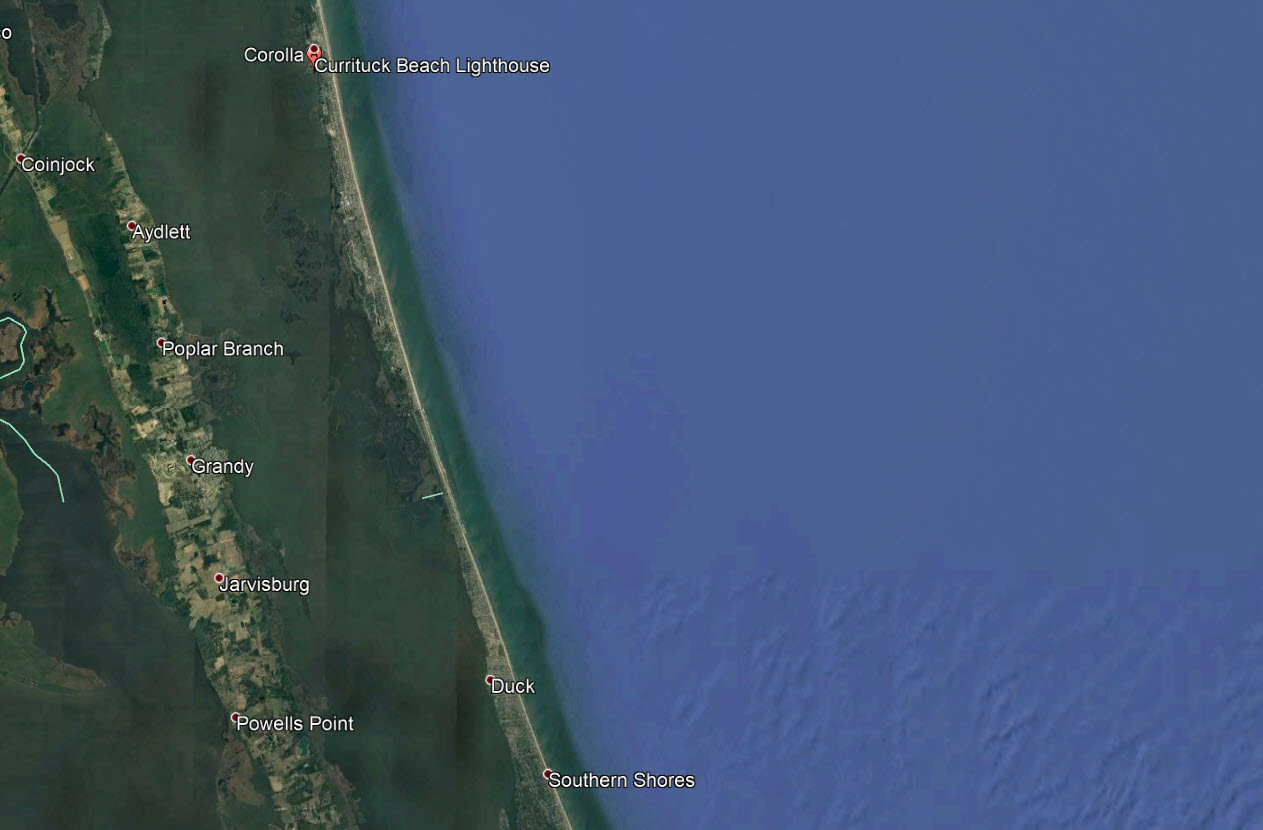

LOCATION OF THE SINKING:

Here is the location of the sinking: Off Currituck Beach

LOST CREW MEMBERS :

| Last | First | Date of Death | Position | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes | George | April 4, 1929 | Crew Member | Portsmouth, VA | |

| Chaney | A.C. | April 4, 1929 | Master/Captain | East Kingham, N.H. | |

| Ferguson | Paul | April 4, 1929 | Crew Member | Norfolk, VA |

SURVIVING CREW MEMBERS :

A partial listing of the surviving crew: Total Crew Lost: 3 Survivors: 7

| Last | First | Position | DOB | Home | Age |

| Carver | George A. | First Mate |