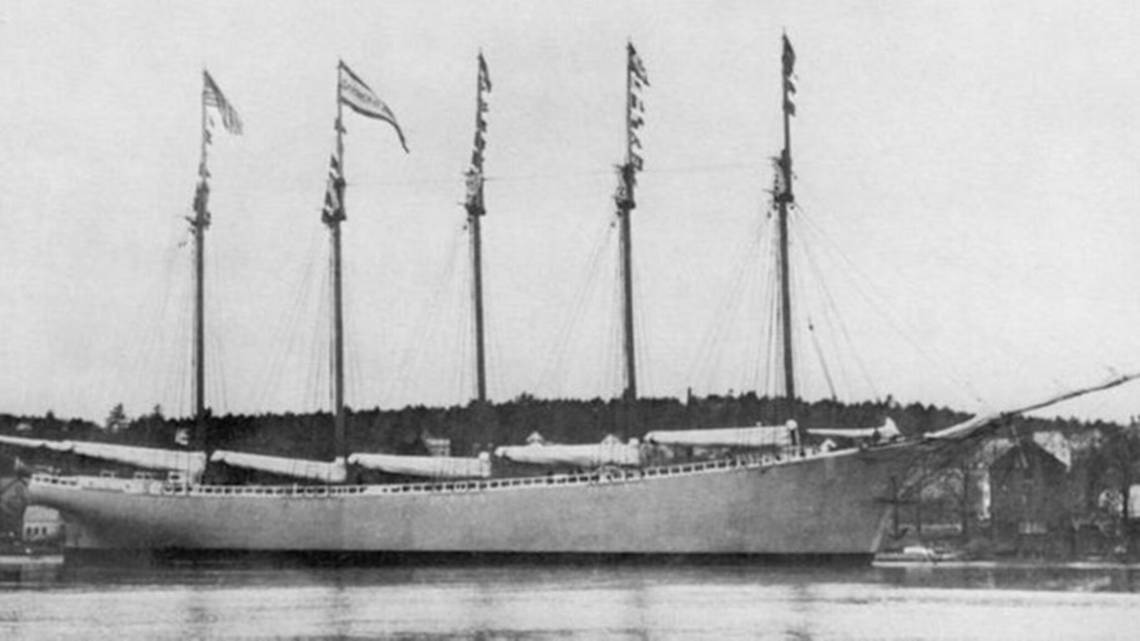

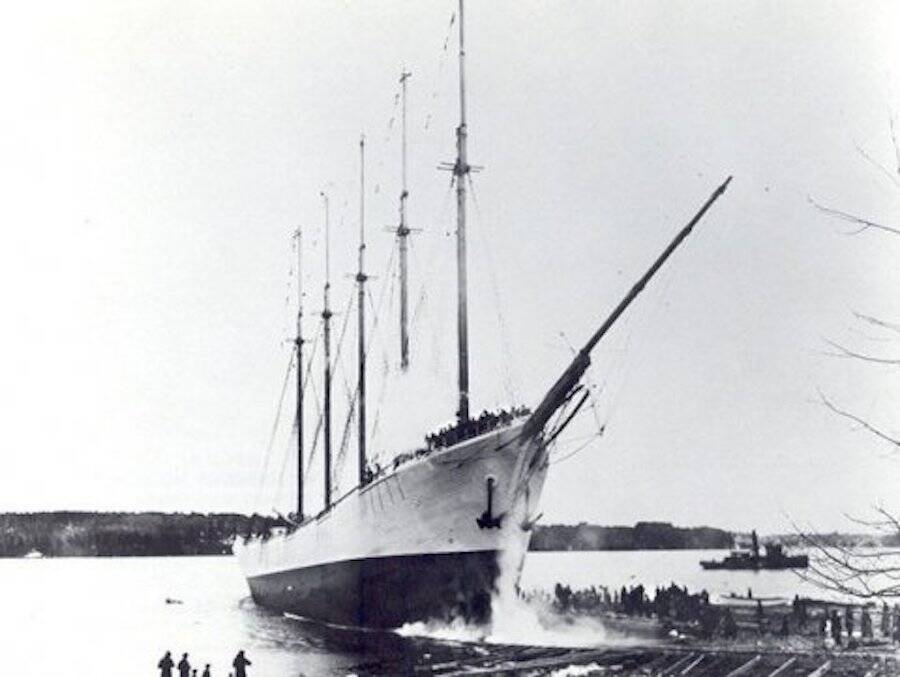

Schooner Carroll A. Deering as seen from Cape Lookout lightship on January 28, 1921. Photo courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

The Sinking of the Carroll A. Deering:

As I began to do research on lost ships in the time period of 1919 -1941, it became a little frustrating attempting to find information about the ships that had been lost off the coast of the Outer Banks during this time period. And then I came across the Carroll A. Deering...now celebrating its mystery's 100 year anniversary. Often referred to as the "Ghost Ship" of the Outer Banks.

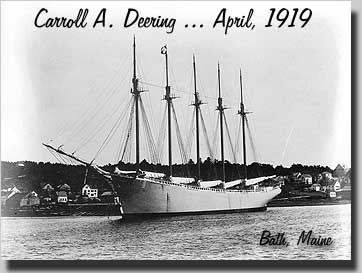

The schooner was launched in 1919 in Bath, Maine. It was named after the son of the owner of the G.G. Deering Company. It was believed to have been a tremendous 5 masts sailing ship. It was outfitted in oak and mahogany and was considered to be rather luxurious considering it was a cargo ship. Onboard was steam heat, a useable lavatory, steam heat, and electricity.

It was first launched into the Kennebec River in Bath, Maine. Its first voyage was to head to Virginia to load the cargo with coal and then transport it to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil under the command of Captain F. Merritt. Merritt had served during WWI and had been cited for bravery under fire when his Deering-built five-masted schooner, Dorthy B. Barrett was sunk by the German U-boat U-117 of Cape May, New Jersey in 1918. He had saved his entire crew during the attack. Its return voyage brought a cargo of corn from Argentina to New York. It made a couple of other trips that the first year.

Kennebec River, Bath, Maine

On July 19, 1920, the Deering sailed arrived in Newport News from Puerto Rico. In August 1920, the ship was scheduled to deliver a cargo of coal to Rio de Janeiro. Onboard was the captain, his son, and 10 men (most were Danish). On August 26, 1920, it had cleared the Virginia Capes. However, Captain Merritt fell seriously ill and the Deering turned back and landed in Lewis, Delaware. There Captain Merritt, along with his son who was to be the first mate, disembarked from the ship. G.G. Deering Company had to move quickly to find his replacement. There he was replaced by a retired veteran captain, Captain W.T. Wormell. Along with Wormell, Charles B. McLellan came aboard as the first mate.

Right away there were problems. Apparently, Wormell and McLellan despised each other as the ship set sail again. Being onboard a ship with close quarters didn't help the conflict between the two men. When the ship arrived in Rio, while his crew was on shore leave, Wormell met with another captain, and old friend Captain Goodwin, who was captaining another cargo vessel. While talking, Wormell spoke of his crew with disdain. However, he did believe he could trust his engineer, Herbert Bates, whom Goodwin knew. The Deering finally left Rio on December 2, 1920, with no cargo aboard.

Early in January 1921 as the ship made a stop in Barbados, Wormell commented to another captain, Captain Hugh Norton that McLellan, "He's habitually drunk while ashore. He treats the men brutally, totally uncalled for." Wormell was asked by another captain if he was worried about mutiny. Wormell didn't think all of the men would turn against him. However, both captains agreed it wouldn't take a whole crew to start a rebellion. To make matters worst, McLellan yelled at the captain (just before arriving in Barbados), "I'll kill you before it's over, old man."

The conflict continued in Barbados while getting drunk at the Continential Café, McLellan was heard loudly saying, "I'll get the captain before we get to Norfolk, I will." His drunkenness and threats landed him in jail. Thinking that McLellan might have learned his lesson, Wormell bailed him out of jail.

Around January 9, 1921, continued their voyage back to the United States. It appears as they made their way back the log entries on the ship's map were filled with Wormell's handwriting. And then things changed...It seems the handwriting was different, it had replaced the writing of Wormell. it continued its voyage up the coast toward North Carolina heading towards the Cape Lookout Shoals.

To add to the mystery, a letter that was circulated among the American Consular Officers at seaports along the Deering's route stated: "On January 29, 1921, the American schooner Carroll A. Deering, sailing at the rate of about five miles per hour, passed Cape Lookout Light Ship, North Carolina...at the time...a man on board, other than the Captain, hailed the Light Ship and reported that the vessel had lost both anchors and asked to be reported to his owners. Otherwise, the vessel appeared to be in very good condition."

Then on January 30, Captain Henry Johnson, of the SS Lake Elan, "sighted a five-masted schooner about two points on our starboard bow, the wind was S.W. moderate and she had all sails set and steering about NNE making about seven miles. We passed her about 5:45 PM about one-half off on our port side we were then about twenty-five miles S.W. true from the Diamond Shoal Light Vessel, from the description of the Deering, we think that this schooner was her but we found not read her name, there was nothing irregular to be seen onboard this vessel but she was steering a peculiar course. She appeared to be steering for Cape Hatteras."

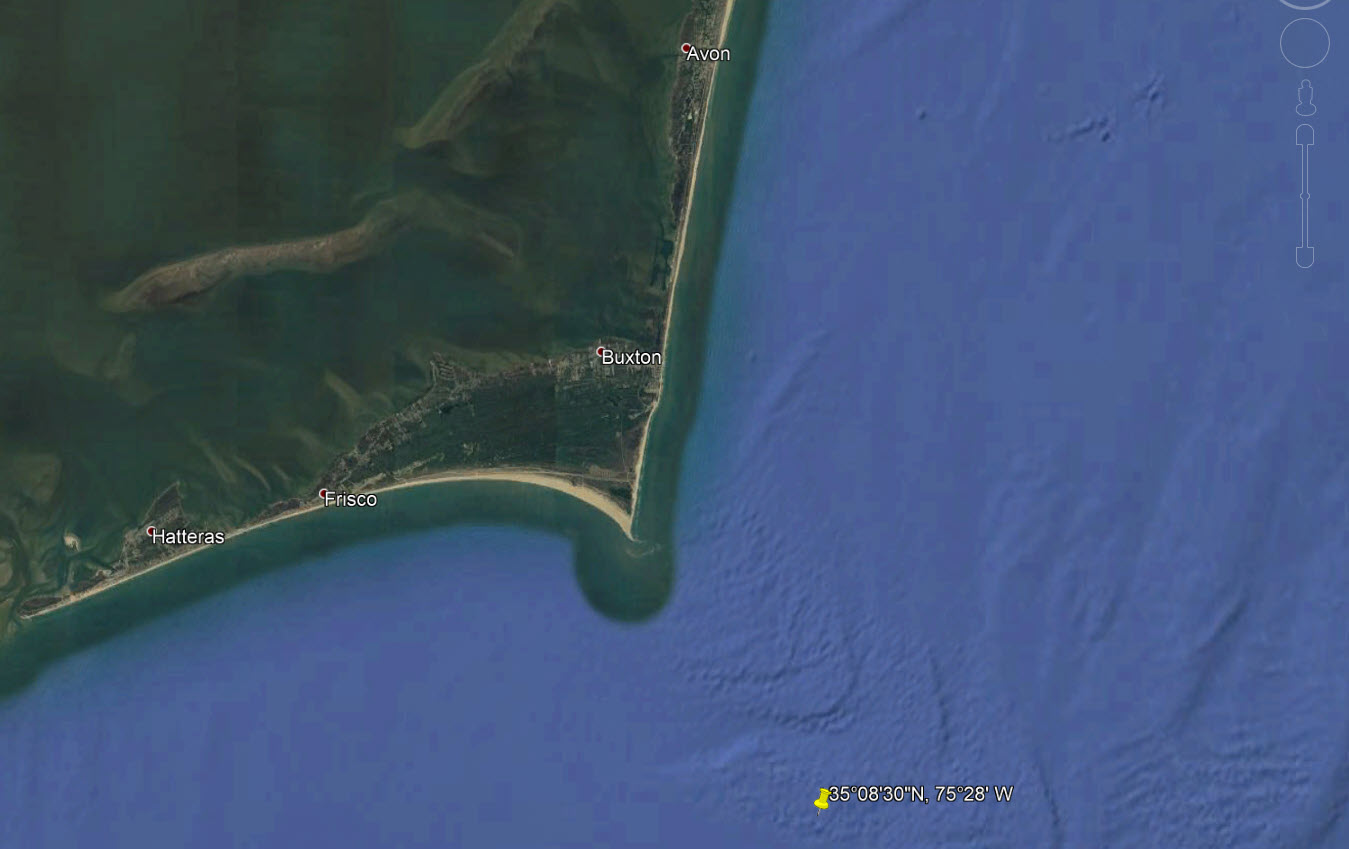

The following day, January 31 at 6:30 AM, Surfman C.P. Brady was on lookout duty at the Cape Hatteras Coast Guard Station when he spotted the Deering, with all five masts set, riding a sandbar on the Diamond Shoals. That early morning the wind was out of the southwest, the sea was rough, and the tide was strong. Two lifeboats from four stations - Big Kinnakeet, Cape Hatteras, Creeds Hill, and Hatteras Inlet - were sent out to attempt to reach the Deering. They arrived in the area by mid-morning. A report submitted by Keeper C.R. Hooper of Big Kinnakeet Station stated that the Deering was "driven high up on the shoal... in a boiling bed of breakers...with all sails standing as if she had been abandoned in a hurry." Another Keeper, J.C. Gaskill of Creeds Hill stated that "she had been stripped of all lifeboats, as ladder was hanging overside."

Given the conditions with the breakers around the Deering, the rescue boats could only get as close as a quarter-mile. From that distance, they couldn't identify the name of the ship. So the following day as the sea was still rough the Coast Guard cutter Seminole was sent out from Wilmington to investigate the situation. Then on February 2, 1921, the cutter Manning and wrecking tug Rescue joined the rescue as they left out of Norfolk.

Due to the weather and sea conditions, it took until February 4 for anyone to be able to board the Deering. By that time waves had been breaking over her deck. The constant bombardment of waves by this time had filled her hold. Also, the seams were so baldly ripped apart there was no way of salvaging the schooner at this point. The rescue team discovered that the steering gear was disabled, charts were scattered about the master's bathroom, and food was set out in the galley and on the stove. They noticed that the ship's log and navigation equipment were missing along with the crew's personal effects. Also, the ship's two lifeboats were missing. They removed what they could from the schooner.

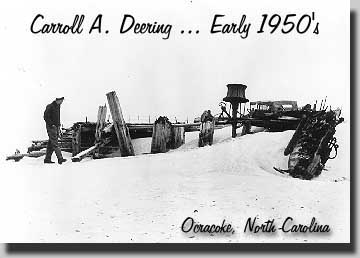

Three weeks later after a severe storm, the Deering was dynamited on March 4 to clear from the shoal since it was considered a navigational hazard. A section of her bow drifted ashore at Ocracoke (see picture below) and became a tourist attraction. Wooden timbers washed ashore on Hatteras Island and were used by local residents to build houses.

So the big question became: What happened to the crew? Over the years there have numerous theories but to this day no one still knows the answers to this question. Five executive branches of the United States federal government started investigations into what happened to the Deering. The branches were the Departments of Commerce, Justice Department, Treasury, State, and Navy. Whereas the Light Ship report regarding the two missing anchors, Shipping Board Commissioner Edward Plummer learned that "both anchors were on the vessel when she was found ashore, the kedge anchor lashed under the bowsprit. Furthermore, the man who hailed the lightship was not the captain, for he had red hair, and according to the records of the owners, there was no red-haired man in the crew."

Their conclusion was that the crew didn't abandon the ship after it was stranded. They drew this conclusion in that they would have lowered the sails prior to leaving to stabilize the ship and help her from grinding on the bottom. Instead, the men must have abandoned the ship prior to it running aground.

There were other suspicious activities surrounding the missing crew. One event reported in the inquiry cam from Cape Lookout flagship. "A short time after the schooner passed the Light Ship, a steamer, the name of which can not be ascertained, which was passing, was asked to stop and take a message for forwarding, and in spite of the numerous attempts on the part of the master of the Light Ship to attract the vessel's attention, no response to his efforts was received."

On April 11, 1921, a local fisherman named Christopher Columbus Gray said he had found a bottle floating in the water off Buxton Beach, North Carolina. Upon "finding" this bottle, he immediately turned it over to authorities. The message stated, "Deering captured by oil-burning boat something like chaser taking off everything handcuffing crew. Crew hiding all over ship no chance to make escape. Finder please notify headquarters, Deering."

Was this the clue to solving the mystery that everyone was looking for? When the captain's daughter, Lulu Wormell, heard of this message, she jumped into action. Since the official investigation really couldn't determine what had happened, this was her chance to get to the bottom of the crews' disappearance. She took the note to the homes of each crew member's relatives, to see if anyone recognized the handwriting. At first, they thought they had discovered who wrote the note. It seemed that the strokes of the writing were those of the schooner's engineer, Herbert Bates. From here the note was taken to a handwriting expert who compared the note with letters written by Bates agreed that the script was similar.

Upon further analysis disputed the resemblance between the note and Bates's handwriting. A follow-up examination determined that the writing style seemed to closely match Christopher Columbus Grey's handwriting. The man who originally found the bottle, Grey, finally admitted he had written the note. After admitting to the forgery, he quickly ran off and hid in the swamp. His intentions were that the publicity he received from finding the bottle would somehow secure him a job at the Cape Hatteras light station.

Meanwhile, as the investigation by the government continued a theory of piracy seems to be favorite speculation. They considered that these weren't any ordinary pirates, instead, they were Bolsheviks. How did they come up with this theory? Up until the time of Deering's grounding as many as twenty ships had been lost of the Carolina coast without a trace. What leads to this suspicion? A bottled message that was suspected to have come from the SS Hewitt stated it had fallen victim to villainous hijackers. The Deering, with its' disappearing crew, added to this speculation.

Why Russain Bolsehviks? In April 1920, Russian mutineers took over the Cuxhaven (German) fishing vessel Senator Schroeder and taken to Murmansk ( a city in Northeastern Russia) and confiscated by the Soviet government. The captain and two officers of the ship were released and returned to Germany. A month later, the vessel was taken back by the crew and returned to Cuxhaven. The two Russian officers who had taken command of Senator Schroeder the month before were tried and sent to prison.

So the investigators took one incident and attempted to apply it to other missing ships. When asked Weather Bureau meteorologist F.G. Tingley believed winter storms were more likely the cause than Russians: "We are not worried about Bolshevikd submarines or pirates."

The big question still hadn't been answered, what happened to the crew? Some like to speculate that it had something to do with the Bermuda Triangle. That some type of paranormal event occurred which lead to their disappearance.

Finally, when the Coast Guard went aboard the Deering, they found the distress signals (two red lights high in the rigging) were lit. It was believed the steamer Hewitt was in the area at that time and may have spotted the signals and rescued the crew. The Hewitt later went down and all the crew was lost in its sinking. Perhaps the crew of the Carroll A. Deering went down with them.

An article on June 21, 1921, of the New York Times, spoke of the disappearance of the two ships. The headline indicated that piracy was involved in the disappearance of three American ships. The article mentions Carroll A. Deering and Hewitt but doesn't name the third ship.

THE SHIP'S SPECIFICS:

| Built: 1919 | Sunk: January 31, 1921 |

| Type of Vessel: Wooden-hulled five-masted schooner | Owner: G.G. Deering Company, Bath, Maine |

| Builder: G.G. Deering Company, Bath, Maine | Power: Sail |

| Port of registry: Bath, Maine | Dimensions: 255' x 44' x 25' |

| Previous Names: |

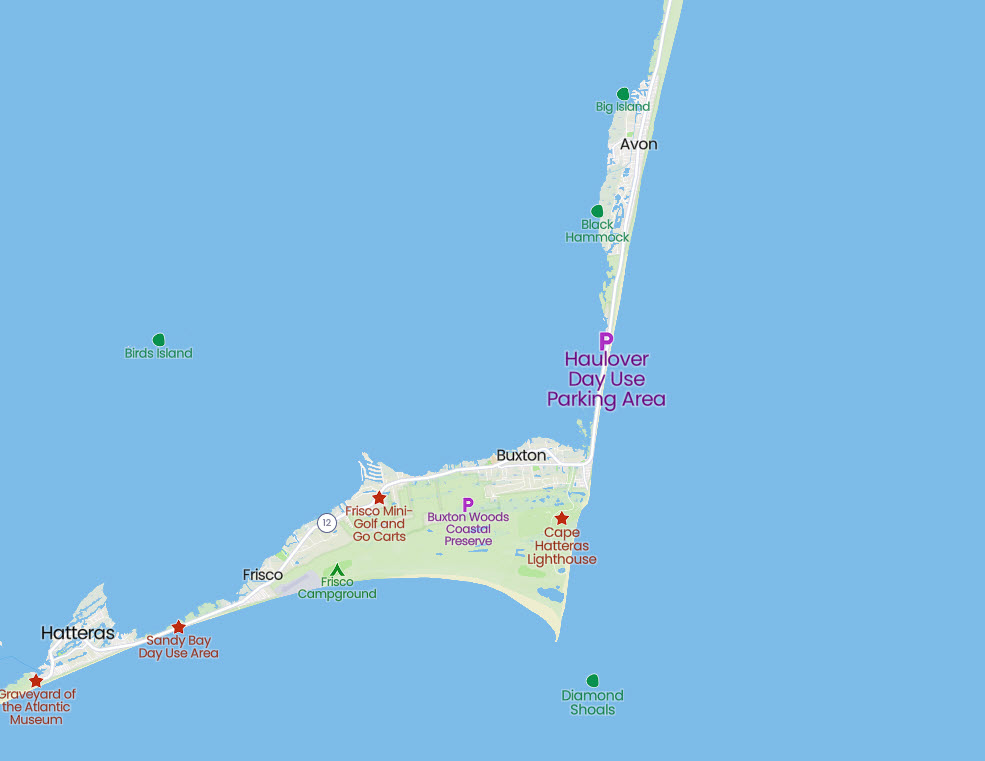

LOCATION OF THE SINKING:

Here is the location of the sinking: Somewhere along the Diamond Shoals 35°08'30" N., 75°28' W.

LOST CREW MEMBERS :

| Last | First | Date of Death | Position | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bates | Herbert | Jan. 31, 1921 | Engineer | ||

| McLellan | Charles B. | Jan. 31, 1921 | First Mate | ||

| Wormell. | W.T. | Jan. 31, 1921 | Captain | ||

SURVIVING CREW MEMBERS :

A partial listing of the surviving crew: Total Crew Lost: 12, Survivors: 0

| Last | First | Position | DOB | Home | Age |

Additional Photos:

|

|

The Carroll A. Deering. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service. |

|

|

|

|

The shipwreck of the Carroll A. Deering, after it crashed near the Outer Banks, N.C. Photo courtesy of Getty Images. |

|