Dixie Arrow.

The Sinking of the Dixie Arrow:

Since it was first built and ready for service in 1921, the Dixie Arrow was very active in the oil-producing areas of the United States: the North Atlantic states, states bordering the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific States (predominately California). Even with the breakout of WW II, the tanker continued to make its usual runs between Texas and the North Atlantic states.

So in keeping with its usual routine, on March 19, 1942, the Dixie Arrow left Texas City, Texas with 86,136 barrels of crude oil heading for Paulsboro, NJ. The captain, Anders M. Johnson, decided to take a course well offshore of North Carolina due to the shallow depths of the shoals along the coast. Unfortunately, this was the area the German U-boats would remain in hiding waiting for any ships to appear in this area.

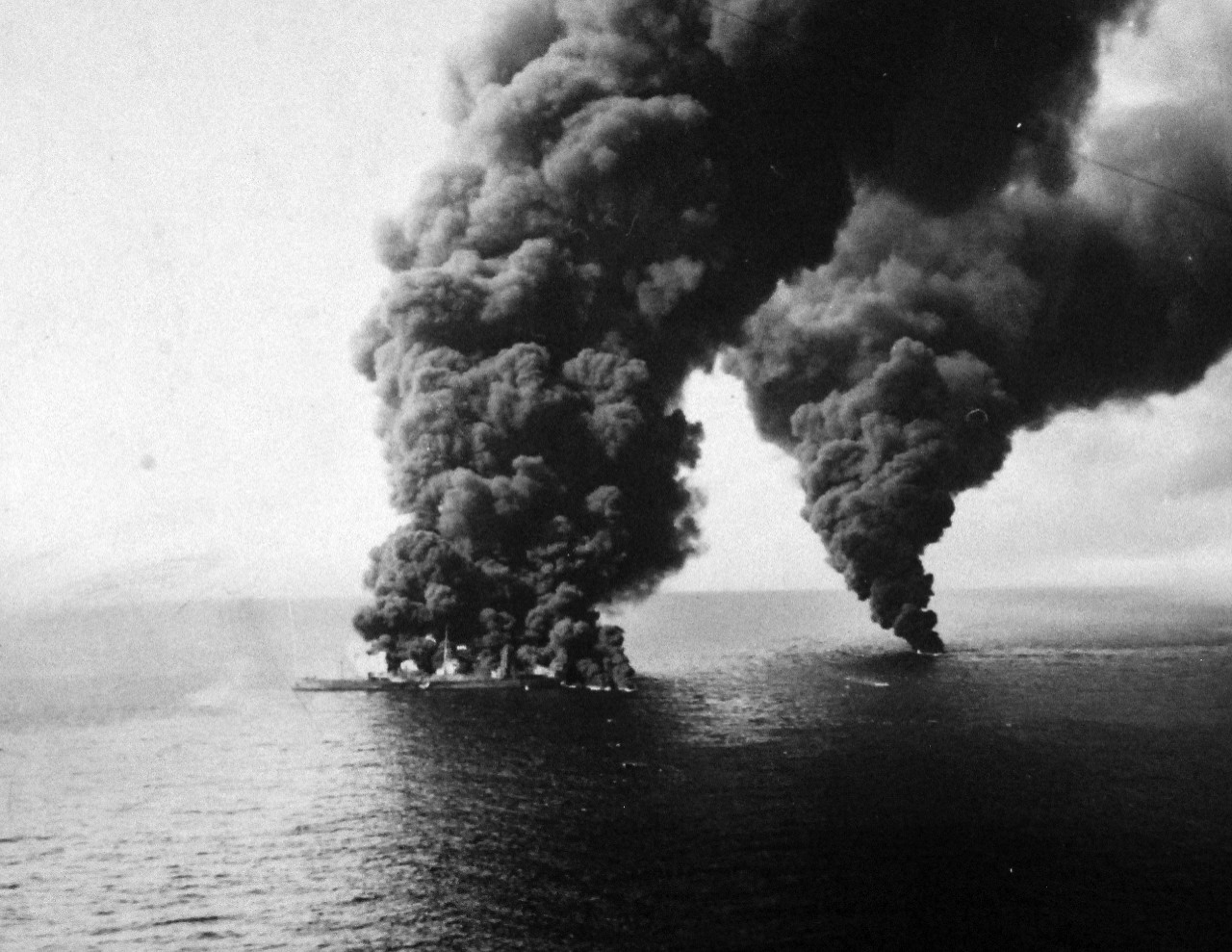

It was around 9:00 AM on March 26, 1942, after making its way around Cape Fear and Cape Lookout entered the area of the Diamond Shoals. Dixie Arrow passed by the Diamond Shoals Light Buoy, 15 miles south of Cape Hatteras, when the attack occurred. The German U-boat, U-71, commandeered by Korvettenkapitän Walter Flachsenberg, fired three torpedoes that struck Dixie Arrow amidships. The first torpedo blew up the forward deckhouse killing all of the deck officers, including Captain Johanson, a radio operator, and a number of other crewmen. No sooner did the first torpedo explode, the other two torpedoes exploded. The two strikes set the ship ablaze and buckled the ship amidships. The fire raged from amidships to stern, as well as spreading over the ocean surrounding the ship. In the raging inferno, two of the four lifeboats were destroyed. A third lifeboat swinging on its davits smashed the deck and crushed one crew member. The final lifeboat was successful in launching with eight crewmen on board. As the lifeboat pulled away from the ship, two men were spotted jumping from the deck of Dixie Arrow and died in the flames. As tanks aboard ruptured, sending burning crude oil over one raft floating near the ship killing all men aboard.

In the chaos, no distress call was transmitted. As noted earlier, the radio operator was killed in the first explosion. Also, the subsequent torpedo blasts knocked out the lights in the engine room. The engine room went totally dark and crewmen scrambled to the deck.

During this panicked situation, there was only one man left aboard alive amidships. This was the helmsman, Oscar G. Chappel. He had been seriously injured during the explosions. Chappel was covered with blood from his severe wounds. With the wheelhouse in flames, he stayed at the helm. He saw that seven men who were forward in the forecastle head were cut off from the lifeboats by the flaming deckhouse. They were surrounded by the burning fuel around the bow. The flames were heading in their direction and were about to kill them all when Chappel turning the ship hard right. This action maneuvered the ship into the wind allowing the trapped men to jump overboard clear of the burning sea of oil. With this brave action on the part of Chappel, he had traded his life for theirs. The flames were now directed at him. As the ship broke in two, Oscar G. Chappel went down with the ship within an hour after it had first been torpedoed.

Fortunately for the surviving crew members, the USS Tarbell was patrolling the area and spotted the smoke that had blackened the sky. A half-hour the Dixie Arrow sank, the USS Tarbell rescued the men in the only lifeboat still afloat, as well as the 14 men floating in the water. Of those 14 men swimming, 7 were saved by Chappel. He was awarded, posthumously, the Merchant Marined Distinguished Service Medal. It read as the following:

Oscar Chappell*

Able Seaman on SS Dixie Arrow 03/26/42

For heroism beyond the line of duty.

His ship, carrying a full cargo of crude oil, was torpedoed three times within one minute. The first torpedo struck directly below the forward deckhouse, and the other two slightly abaft this point causing the ship to buckle amidship. The explosions immediately ignited the combustible cargo; all amidship and astern sections of the ship were enveloped in flames, and the fire rapidly spread over the ocean surrounding the ship. Injured by the explosions, with blood covering his head and shoulders, Chappell stuck to his post at the helm even though the wheelhouse was in flames. He saw seven of his shipmates trapped on the forecastle head. Driven by the wind, the fire was sweeping toward them over the deck, and all escape was cut off by water-borne flames surrounding the bow. Fully aware of his own desperate situation, Chappell put the helm hard right and held the ship into the wind deflecting the flames upon himself, but enabling his shipmates to jump overboard clear of the blazing sea of oil. Placing his own safety beyond all consideration, his last thought and act was to assure the survival of his imperiled shipmates.

His magnificent courage and selfless disregard of his own life constitute a degree of heroism which will be an enduring inspiration to seamen of the United States Merchant Marine everywhere.

For the President

Admiral Emory Scott Land

The rescued men were taken to Morehead City, One survivor, Victor Hoffman, after his rescue, stated, "I had my hat on when I jumped overboard, and here it still is, right on my head. I'm going to put it in the parlor in a glass case, the way some folks pout their best silver."

It should be noted that in my research, I found several different reports about when the ship actually sunk. One indicated with an hour, another within two hours, and a final one stated that it remained afloat throughout the day, filling the sky with black inky clouds of smoke and soot that were visible for miles. The later report stated that official reports state that the Dixie Arrow's sinking went unobserved. It goes on to say that the burned-out hulk drifted right into the Hatteras minefield, perhaps detonating a friendly mine before sinking.

On March 30, 1942, a Coast Guard plane reported seeing three masks showing above the surface. After the sighting, the buoy tender, Orchid was sent to the scene where it established a red nun buoy. For the next year, the Dixie Arrow became target practice from the nearby Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point. By 1943, the masks had been destroyed from the target practice. In 1944, Navy divers went to the wreck to assess the situation. At first, they thought they had discovered the Ario. However, after recovering the ship's bell, they were able to confirm it was the Dixie Arrow. The remains were demolished with explosives and wire-dragged to a least depth of 43 feet.

THE SHIP'S SPECIFICS:

| Built: 1921 | Sunk: March 26, 1942 |

| Type of Vessel: Tanker | Owner: Socony-Vacuum Oil Company |

| Builder: New York Ship Building Corp., Camden, NJ | Power: Oil-fired steam |

| Port of registry: New York, NY | Dimensions:468' long x 62' wide x 32' deep |

| Previous Names: None |

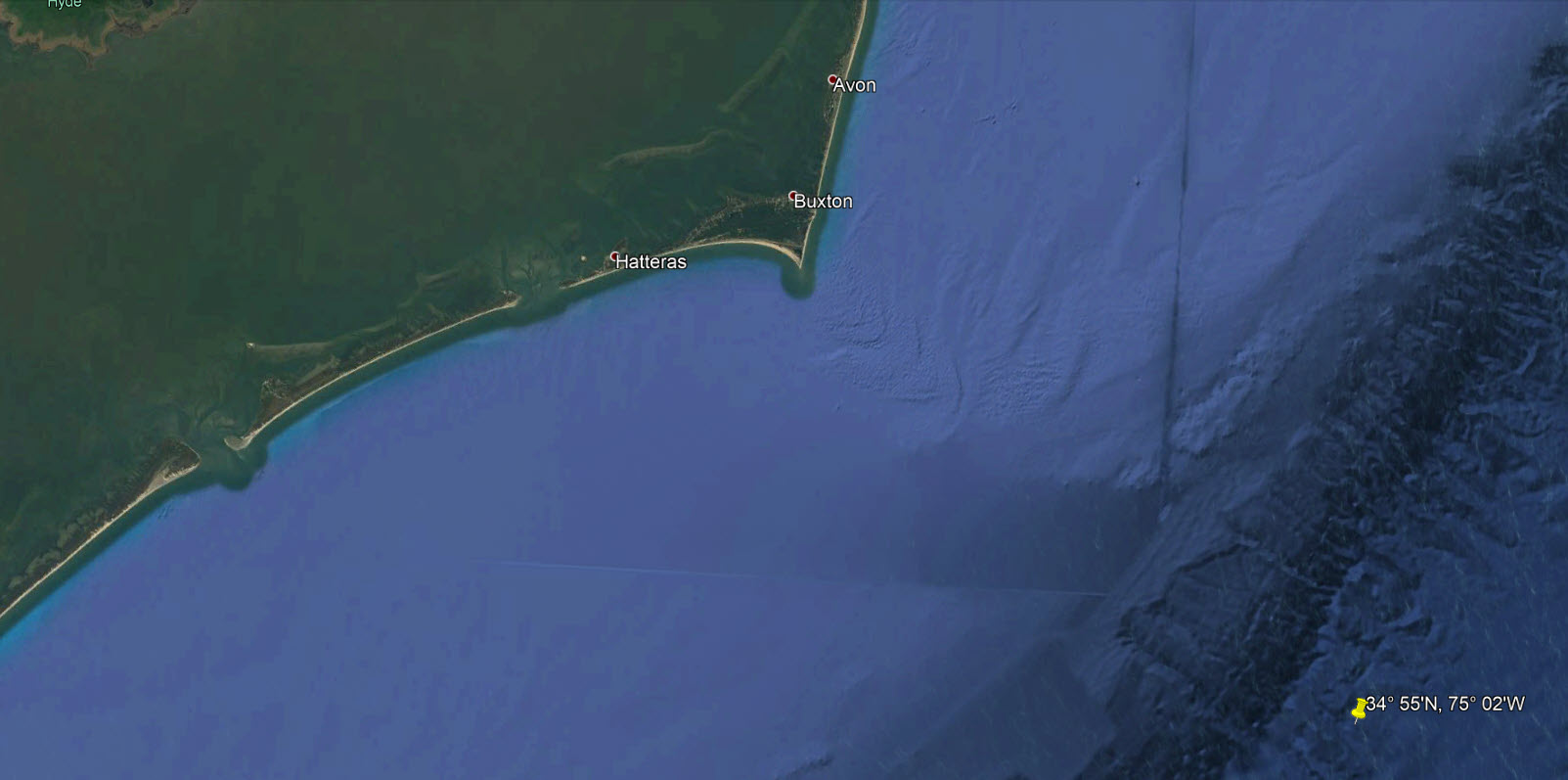

LOCATION OF THE SINKING:

Here is the location of the sinking: 34° 55'N, 75° 02'W

LOST CREW MEMBERS :

Total Lost: 11, Survivors: 22

| Last | First | Date of Death | Position | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Chappell | Oscar Gaston | March 26, 1942 | Able Seaman | Normangee, TX | 29 |

| Collins | William Parker | March 26, 1942 | Chief Mate | Dorchester, MA | 46 |

| Dailey, Jr. | Horace Eugene | March 26, 1942 | Third Mate | Boston, MA | |

| Flynn, Jr. | James Joseph | March 26, 1942 | Radio Operator | Philadelphia, PA | 21 |

| Goark | Velontie John | March 26, 1942 | Messman | Watervliet, NY | |

| Honkala | Arthur | March 26, 1942 | Messman | Eveleth, MN | 35 |

| Johanson | Anders Melin | March 26, 1942 | Master/Captain | Brooklyn, NY | 52 |

| McNamee | George Robert | March 26, 1942 | Second Mate | Oceanside, NY | 46 |

| Norheim | Ivar Martinius K. | March 26, 1942 | Chief Cook | New Orleans, LA | 42 |

| Sawyer | Wilbur E. | March 26, 1942 | Ordinary Seaman | Beaumont, TX | 33 |

| Shannon | Thomas Joseph | March 26, 1942 | Ordinary Seaman | Beaumont, TX |

*Awarded the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal.

SURVIVING CREW MEMBERS :

A partial listing of the surviving crew:

| Last | First | Position | DOB | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoffman | Victor | ||||

| Myers | Paul | Crew Member |

Photos of the Naeco:

|

|

|

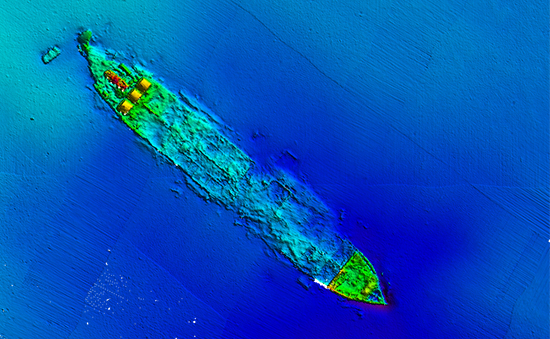

The bow section of the Dixie Arrow. Photo courtesy of Hoyt, NOAA. |

Rudder post and stern section. Photo courtesy of Hoyt, NOAA. |

|

|

|

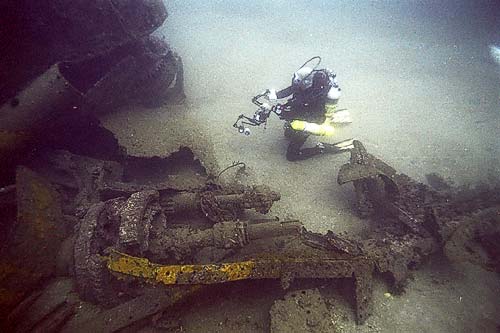

MNMS archeologist studying the bow section of Dixie Arrow. Photo courtesy of Hoyt, NOAA. |

|

|

|

|

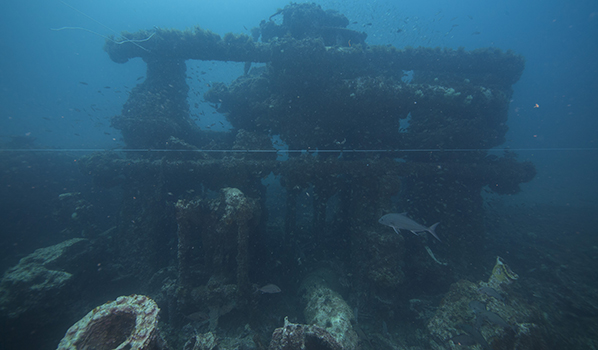

The remains of the tank walls provide the highest relief on the wreck. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

|

Stern machinery - post-Hurricane Isabel (2003). Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Stern machinery circa 2002. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Connecting rods at the base of the engine. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Engine towers over the bottom. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

The diver rounds the bow. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Rudder post at the stern. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Engine. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Box on the starboard side of the stern. Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

Diver kneels at the stern - most of this was under sand prior to Hurricane Isabel (2003). Photo courtesy of Paul M. Hudy. |

|

Dixie Arrow burning off Cape Hatteras after being torpedoed by U-71. Photo courtesy of National Museum of the U.S. Navy

Dixie Arrow burning off Cape Hatteras after being torpedoed by U-71. Photo courtesy of National Museum of the U.S. Navy I

I