The Sinking of the Tzenny Chandris:

The ship was first named the Eastern Packet when it was built in 1920 in Kobe, Japan. After several years of service and the toll the depression had on shipping, she was docked on the James River in Virginia to rot away the remainder of her life. Then John Chandris, a representative of a Greek shipping syndicate purchased the Eastern Packet for $64,000 and renamed it Tzenny Chandris. His idea was to use the ship to transport goods to Europe. He enlisted a crew from his home country of Greece. The ship was quickly prepared for its first voyage even though it really hadn't been well maintained. It was towed to Norfolk to make needed repairs. Shipyard workers, along with the crew, began to chip away the rust, paint and getting her machinery back in working order. The engines were overhauled and their wireless communications were put back to being functional, though not the best or most modern. The lifeboats were cleared of rust and patched up.

The crew aboard, as mentioned previously, were all Greek except for Joseph Corrie, a forty-six-year-old English coal passer. At the helm was Captain Geoge Couhopadelis. Most of the crew hadn't been to sea for quite some time. The wireless operator was young and inexperienced. But they were ready to head out.

While in Norfolk, the Tzenny Chandris loaded several thousand tons of scrap iron and a small stock of sheep, hogs, and fowl. It then made stops in Hampton Roads and Newport News to pick up more cargo. On October 27, 1937, she left Newport News and headed to Morehead City. On November 11, she picked up her last load of scrap iron and attempted to head out. By that time she was loaded with 9,010 tons of scrap iron. As she headed out of the pier at Morehead City it was discovered that with all the weight aboard she got stuck on the bottom. The only recourse was to await high tide so she could float away free. The wait lasted until the following morning, November 12, 1937, as it headed out to Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Getting stuck on the bottom should have been an omen of things to come. By the time the Tzenny Chandris passed Cape Lookout, she was already taking on water. "We begged the Captain to turn back to some port when we found she was leaking," coal-passer Corrie stated later, "but he said the pumps would take care of the water."

Meanwhile, a nor'easter began to blow between Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras. This storm only added to the ship's problems. "She commenced listing to starboard before we got into the storm," Corrie said. "When the storm hit us Friday afternoon water came pouring from somewhere in the coal bins, shooting through a little door that coal fell through. When I went on watch Friday night I didn't want to go down in that place, but the Captain persuaded me to go. I couldn't swim and when the water came rushing in that place again, I went on the deck. About that time the engine went off fix and all lights went out." In the heavy seas, the ship rolled to starboard and a large portion of the scrap iron shifted. By then the Tzenny Chandris sustained a fifteen-degree list.

Also at this time, the seas were crashing across the ship's deck and several of the lifeboats were swept away. Kostas Palaskas, a twenty-five-year-old third engineer, along with others had been "pleading with the captain for five hours" to send an S.O.S. Apparently, during the chaos one of the seamen attacked Captain Couhopadelis and bite him in the face before being the others were able to beat him off. The Captain finally relinquished and gave the order to send the S.O.S out. However, the young operator in a state of panic was unable to send it promptly. The first report was that Palaskas had said he threatened the operator at knifepoint to get the message off. Reportedly he said, "I told him I would kill him if he didn't send that S.O.S." However, an article published in the New York Times on November 17, 1937, states that Palaskas retracted this statement. Testifying before Dr. C.D.J. MacDonald, city coroner of Norfolk, in a bedside inquest at the Marine Hospital, Palaskas explained that he did not threaten the radio operator and that the knife in his hand at the time was there innocently, as he had been using it previously. In speaking through an interpreter he also denied that the ship was unseaworthy. The S.O.S. finally went out at 4:06 AM on Saturday, November 13, 1937. The message was sent out several times and picked up by shore stations and ships in the area. The problem was that the operator never gave the location of the Tzenny Chandris. One ship during the night passed so close that the captain attempted to signal it with a flashlight. By 5:15 AM radio transmissions had fallen silent.

Captain Couhopadelis finally ordered the crew to put on life belts. He ordered the lifeboats lowered. However, some of the crew didn't wait for the lifeboats and jumped over the side of the ship. Corrie was the last man to leave the sinking ship. "The rain and wind made so much noise your couldn't hear anybody yell," he said. "I waited there on deck. I didn't want to jump because I had seen some of the fellows jump and they looked like they got hurt. The ship lurched once and went over on her side. She lurched again and went over flat on her side, level as a floor. Then is when I walked down and jumped. I was caught in the suction but I had to open my mouth to breathe and every time I did I took in seawater. It seemed like a year before I came back up." At the time the ship was abandoned they were approximately forty miles northeast of Diamond Shoals Lightship.

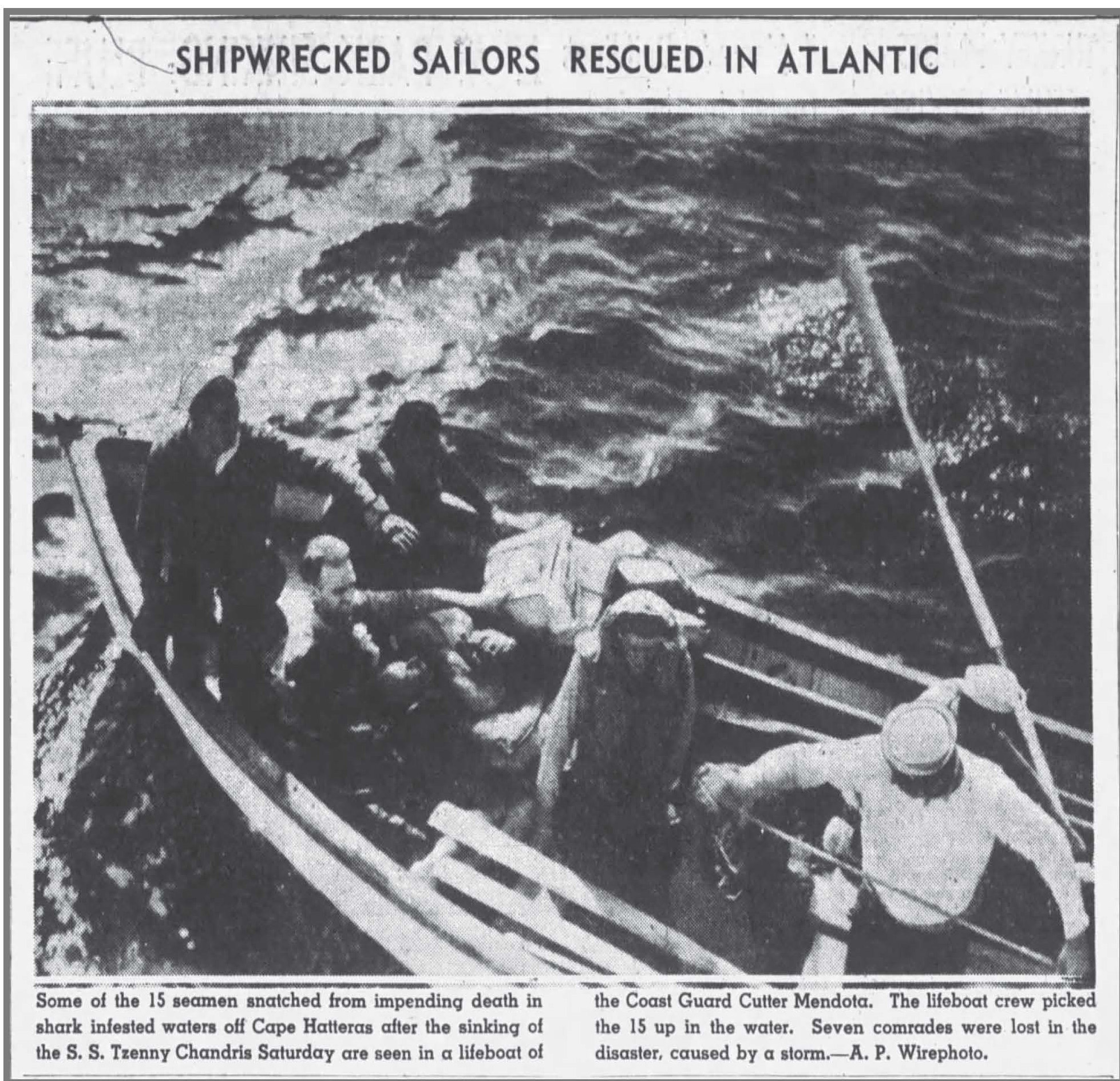

An article in the Oakland Tribune dated November 15, 1937, stated that "Balaskas, rescued from shark infested waters off Cape Hatteras with 14 other crew members by the Coast Guard cutter Mendota."

"Hurried into the seas, the men clung to life rafts and wreckage for 32 hours before they were picked up. During the time they were battered by the seas, they fought off sharks which attacked them. The survivors were able to beat off the man-eaters by kicking at them. Joseph Corrie, an English survivor, related. The sharks, however, tore apart the bodies of the seamen who had drowned."

Corrie told about being battered by mountainous seas for more than 30 hours while he clung to the wreckage. "The sharks kept brushing up against me," he said, "but when I kicked out against them with my feet, they would go away. They seemed to attack the bodies of the dead men rather than the men who were alive. But when the Mendota picked me up, I was just about ready to give up. This was my first trip to sea and I think it's going to be my last."

"One of the 16 originally rescued died while en route here. The Mendota also brought back three bodies that were taken from the water." Another six men were picked up by the American tanker Swiftsure.

At 10:30 AM on Sunday, November 14, 1937, Lieut. A. C. Keller spotted the survivors from his naval plane 90 miles east of Kitty Hawk. He dropped smoke bombs and plunged down in dangerous power-dives which frightened off the sharks long enough for the Mendota to reach the scene, pull the exhausted mariners from the water 40 miles from the grave of the luckless Tzenny Chandris.In his investigation, Dr. MacDonald went on to render a verdict that four of the dead, who were brought to port came to their death "as a result of exposure and exhaustion resulting from the sinking of the steamer Tzenny Chandris."

THE SHIP'S SPECIFICS:

| Built: 1920 | Sunk: November 13, 1937 |

| Type of Vessel: Freighter | Owner: |

| Builder: Kobe, Japan | Power: |

| Port of registry: | Dimensions: |

| Previous Names: Eastern Packet |

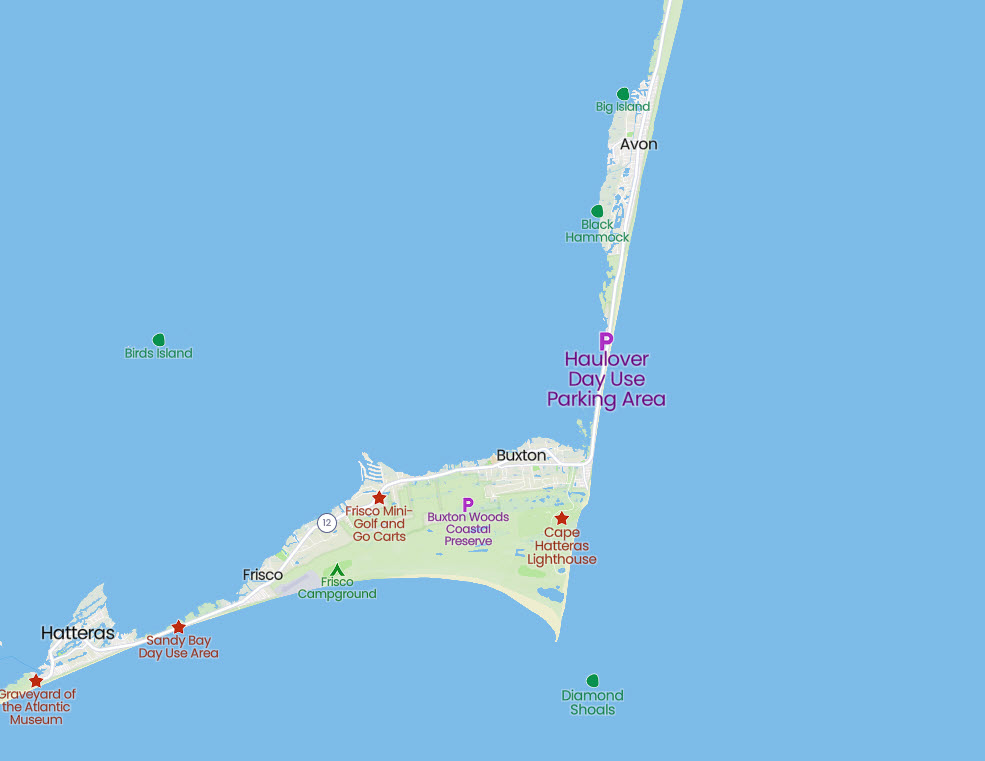

LOCATION OF THE SINKING:

Here is the location of the sinking: approximately forty miles northeast of Diamond Shoals Lightship

LOST CREW MEMBERS :

| Last | First | Date of Death | Position | Home | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frangoulis | November 14,1937 |

SURVIVING CREW MEMBERS :

A partial listing of the surviving crew: Total Crew Lost 7: Survivors: 21

| Last | First | Position | DOB | Home | Age |

| Corlos | Demetrius | Chief Officer | |||

| Corrie | joseph | Coal Passer | |||

| Couhopadelis | George | Captain | |||

| Dacoglu | Alexandria | Second Mate | |||

| Kakares | Martheas | Chief Engineer | |||

| Palaskas | Kostas | Third Engineer |

Additonal Photos of Tzenny Chandris:

|

C. Maroulis, the interpreter for the Ledger-Dispatch, listening to George Coufopandelis' account of the shipwreck of the Greek freighter, Tzenny Chandris.Photo courtesy of Virginian Pilot Photograph Collection. |

|

|

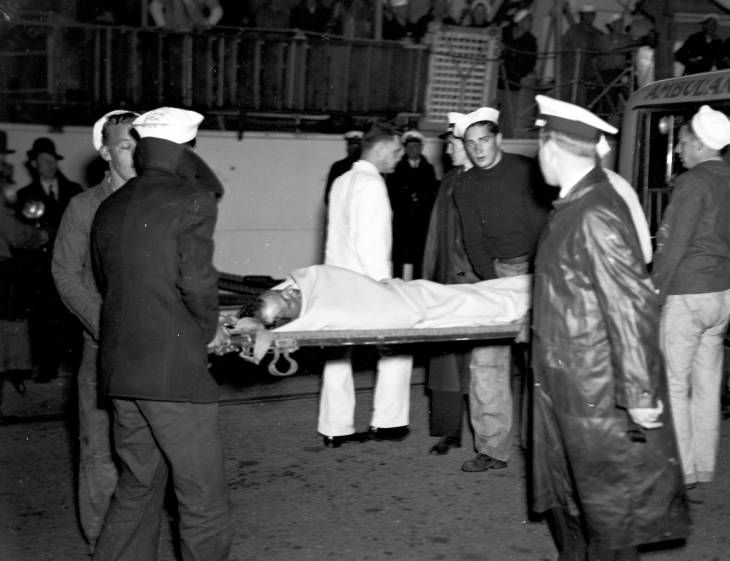

A survivor from the shipwrecked Greek freighter Tzenny Chandris being carried on a stretcher from the U. S. Coast Guard cutter Mendota at the Norfolk Naval Base in Norfolk, Virginia.Photo courtesy of Virginian Pilot Photograph Collection. |

|

|

|